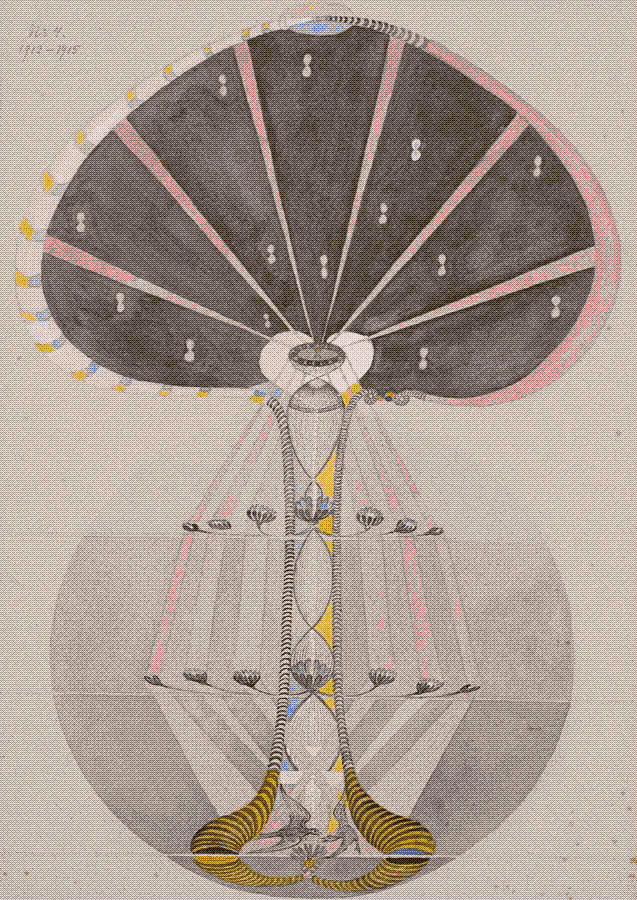

Hilma af Klint, while relatively unknown during her lifetime, has become something of a mythical figure in the art world. Now widely regarded as one of the earliest pioneers of abstraction, af Klint was a Swedish artist who was active in the early 20th century. Her status as a legend does not only derive from the fact that she was painting purely abstract pieces before Kandinsky, but also from her mode of working: she allegedly received the ideas for her pieces through mediumship, the spiritual concepts delivered from the entities whom she called the “High Masters.” Her eccentric methods and esoteric work fascinate audiences and critics today more than ever, but often excluded from discussions about her body of work is the series of paintings called The Tree of Knowledge. This series consists of eight watercolor paintings created between 1913 and 1915, each of which represents a tree-like shape embedded with various patterns and symbols. The spiritual imagery of this series is striking and powerful. Through these paintings, af Klint conceives of alternative knowledge systems which emphasize wholeness, synthesis, and the androgyne. These systems directly challenge and contradict the binary modes of knowing and categorizing which prevailed in a time dominated by scientific and so-called “masculine” thinking.

The existing literature about Hilma af Klint naturally tends to focus on the spiritual nature of her work, in addition to her methods of abstraction. Her work captures the attention of not only art critics, but those who study religion, philosophy, and psychology. Most tend to agree that the bulk of her work resembles complex spiritual diagrams, utilizing shape, color, and pattern to convey esoteric concepts. Scholars have identified thems of duality, synthesis, transformation, harmony, transcendence, and the relationship between chaos and order across her work. Much effort has also been expended to catalog the multitude of religious motifs and symbols in af Klint's work, as she incorporated elements from Christianity, Buddhism, Norse Paganism, and the new religious movement known as Theosophy into her art[1], to name only a few of her wide-ranging influences[2]. Though af Klint and her work were seen as nothing more than outlandish oddities during her lifetime by the majority of the art world, modern critics and scholars have approached her with far more respect, celebrating both the ingenuity of her compositions and the fascinating process that led to their creation.

The existing research also consistently refers to the "androgyne," which figures prominently into af Klint's work and refers to a spiritual fusion of feminine and masculine energies into a third, androgynous energy. Androgyny can typically be defined as a quality that is neither feminine nor masculine, or is the combination of both. The "androgyne" of spiritual thought can be conceptualized as "an integrated new state that is a 'third' position" which is achieved through a "process of development [that] emerges through a rhythm of polarity"[3]. Put more simply, the androgyne is the state of complete union and wholeness, and can symbolize transcendence, divinity, the primal origin, or even "spirit" itself. Many cosmologies view androgyny as the initial state of life[4]. Af Klint repeatedly engages with this symbology in ways both vague and explicit. Specifically in her Tree of Knowledge series, she utilizes this symbology to conceive of alternate knowledge systems derived from wholeness and synthesis. And just as nonconformity to the gender binary presented a challenge to prevailing social powers at the time, so did nonbinary knowledge systems such as the ones af Klint imagines into being through this series.

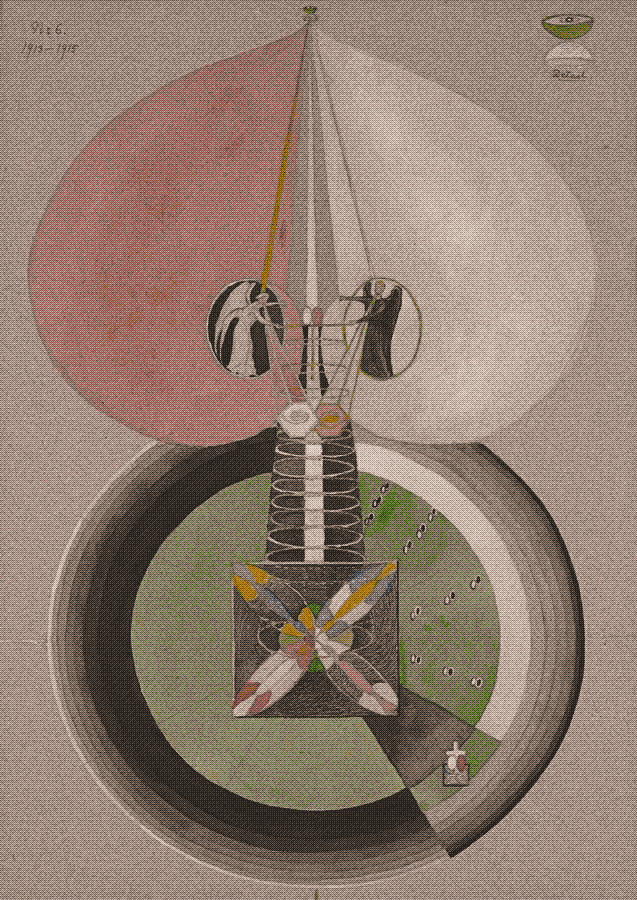

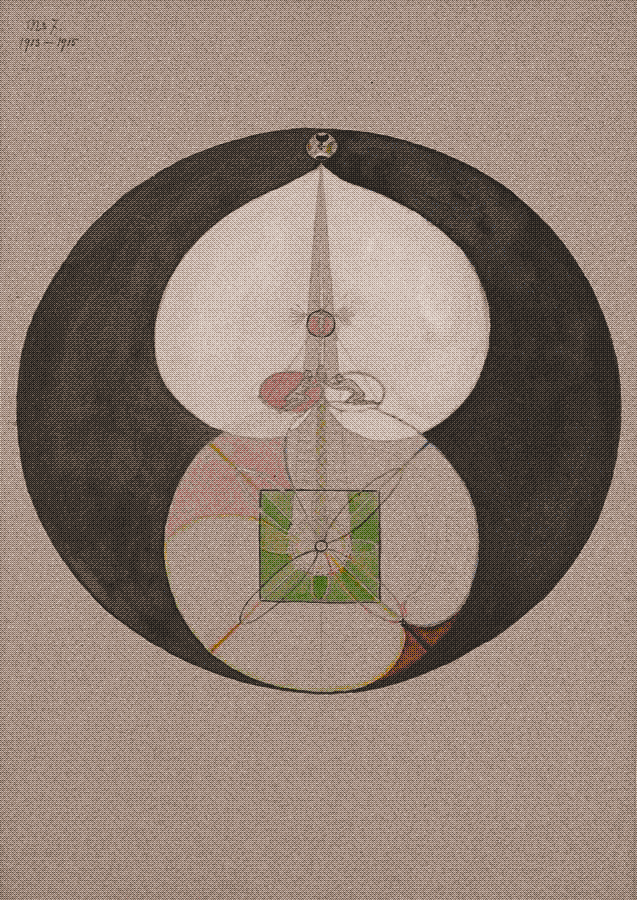

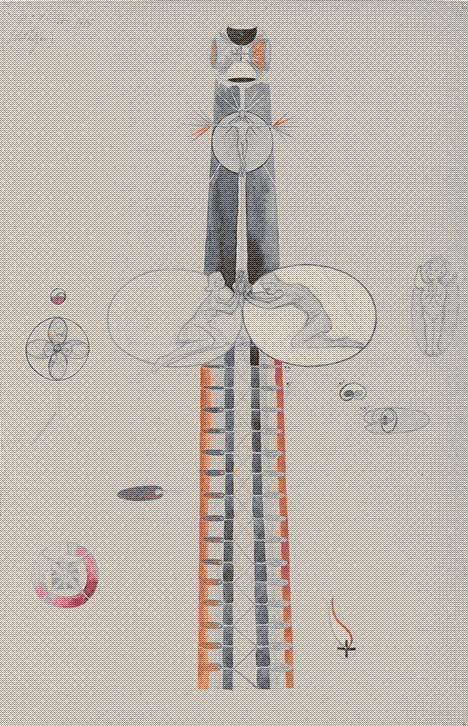

Af Klint dissolves the gender binary in her work, as she positions the androgyne as the ultimate essence of spirit and life. This disruption of conventional gender binaries is present through the entire series in subtle ways, but becomes explicit in the final three entries of the series, Tree of Knowledge numbers 6, 7a, and 7b. In Tree of Knowledge, No. 6, there is an angelic figure positioned on either side of the abstract tree. While the figures are too small to ascertain any gendered qualities, af Klint is known for symbolizing gender through color, and "black and white... represent masculine and feminine, according to her colour code"[5]. Hence, the rightmost figure is presumably masculine while the one on the left is feminine. Emerging from each figure's hands are a sort of beam, and these beams meet in the middle of a spiral shape which leads down to the complicated mandala pattern in the bottom half of the painting. This visualizes a fusion of dual energies, different yet complementary, which funnel down into a singular result which is greater than the sum of its parts[6]. Tree of Knowledge, No. 7a and No. 7b require even less analysis of color and symbol in order to see the formation of the androgyne. Both paintings feature a female figure on the left and a male figure on the right, with a line emerging from each of them, joining at a genderless figure positioned above them. What is seen more clearly in No. 7b is the array of bright colors emerging from the hands of the genderless figure. Both these colors and the positioning of the androgynous figure combine to suggest that this state of being is one of transcendence and spiritual or divine energy. The way the masculine and feminine figures reach for each other through the boundaries of the shapes they are encapsulated by implies a search or yearning for this merging; that for them, to break away from the restrictive binary and fuse togehter would mean ultimate freedom or ascension. Af Klint painted this series in a time when the strict definitions of man and woman in Western-colonial society were staunchly defended. To deny adherence to either gender, transfer between the two, or suggest the ability to inhabit both, was not culturally acceptable. This immediately points to a tension between af Klint and the social norms around her, which will persist into the other challenges she presents in this series.

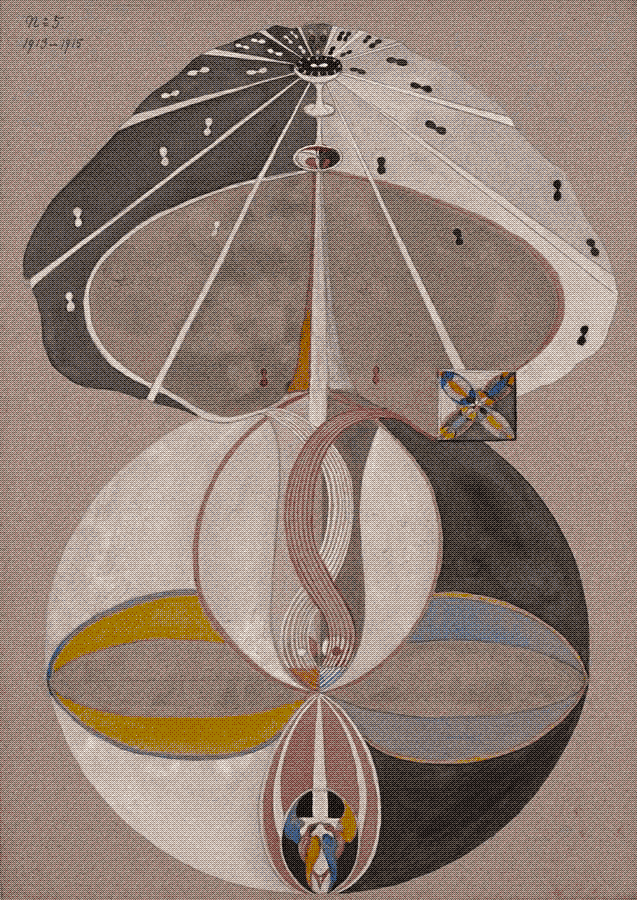

One such additional challenge to the status quo is af Klint’s portrayal of the human and the animalistic bleeding into each other, situated as interrelated rather than separate. While humanoid figures are featured in the final three paintings, paintings one through five feature birds instead. Especially given that the sixth painting features humanoid figures with wings, taken as a whole, the series appears to represent the transformation of birds into people, or perhaps, the birds and the people are simply different representations of the same latent energies. Additionally, all of these living forms blend and merge with the tree-like figures that contain them, the birds at times merging so completely that it is hard to even tell they are there at first glance, such as in Tree of Knowledge, No. 5. Historical accounts report that af Klint “was drawn to Darwin's theory of evolution,” and her interest in Buddhism could indicate considerations of reincarnation and cyclical existence [7]. The persistent incorporation of circles, spirals, lemniscates, and ouroboros all certainly seem to indicate a fascination with cyclical and infinite processes in af Klint’s art. Such a representation of existence results in an unclear delineation between the species. If people can easily become animals, or perhaps always have the potential to be an animal, there is no truly significant boundary between the human and animal kingdoms. Within the systems she presents, af Klint sees no superiority of one species over another, painting them all as if they are simply different incarnations of the same energies. While such an ideology is not revolutionary to the modern person, it is important to consider that Darwin’s theory of evolution was not universally accepted by scientists until the 1950s, and it took even longer for it to earn widespread cultural acceptance [8]. Thus, during af Klint’s lifetime, a large quantity of people took issue with the idea that humans could be related to animals, or that we ourselves are animals. Many religions, cultural institutions, and governmental powers were (and often still are) invested in protecting the idea of a clear boundary between human and animal; a boundary which af Klint repeatedly transgresses in her Tree of Knowledge paintings in favor of representing spiritual links between all life.

In addition to theories of evolution, the occult maxim of "as above, so below" figures into the formal qualities of the Tree of Knowledge paintings and further confuses binaries. The phrase “as above, so below” most likely meant to af Klint that all different planes of existence correspond to each other and reflect each other [9]. In simpler terms, the internal reflects the external: a molecule mirrors a galaxy, for example. Taken temporally, it also means that things end the way they begin. This temporal aspect of “as above, so below” features in af Klint’s paintings in the form of the ouroboros — that being, the symbol of a snake eating its own tail, which is often meant to represent the symmetry of beginnings and endings. Af Klint does not explicitly depict snakes, but in Tree of Knowledge, no. 3 and no. 4, a snake or worm-like shape loops around the tree, meeting both at the top and at the root. Af Klint playfully enacts the “as above, so below” philosophy through her use of symmetry and the cohesive interweaving of seemingly disparate pieces. Each painting contains a top portion, the branches of the tree, and a bottom portion, the roots, which reflect each other imperfectly but harmoniously. For example, the first few entries of the series feature infinity symbols patterned onto the top portion, and these forms are then reflected in larger form in the bottom half of each painting. The series taken as a whole does not evoke a sense of numerous different trees; in fact, it appears as if each piece represents the same exact thing, with another layer stripped from it, until it reaches its innermost core in 7b. This can be seen in how the small, patterned square on the right hand side of number 5 becomes enlarged and placed at the bottom of number 6, or how the symbol of a chalice appears and moves among different placements and sizes throughout the entire series, slightly changing in appearance each time and yet clearly the same object. The implication af Klint makes through these formal choices is that the Tree of Knowledge can be, and is, all of these things at once. (Note that she didn’t call it Trees of Knowledge). It does not have to be any one thing. To believe that one thing can actually be many things simultaneously is, by necessity, to reject the existence of any form of binary.

Furthermore, in this series, af Klint envisions a knowledge system consisting of both the spiritual and the scientific, rendering them as compatible rather than opposing. As noted in much of the scholarship on her work, her pieces resemble diagrams. In fact, she had an interest in botanical and scientific drawing, which she dabbled in herself, so this resemblance is no accident [10]. The Tree of Knowledge series is perhaps one of her most diagrammatic. For instance, in the top right corner of Tree of Knowledge, No. 6, af Klint went out of her way to include a detail image of the tiny chalice from the top of the tree, the kind of thing one would typically only expect to see in a scientific drawing of a plant or animal specimen. Scientific drawings are conventionally accepted as a mode of identification, categorization, and demystification. Yet af Klint utilizes this mode in conjunction with abstraction, esoteric symbology, and overall obscure imagery. Rather than using science to demystify spirituality, she uses spirituality to mystify scientific modes of thinking and knowing. Af Klint’s series simultaneously encourages understanding while also opposing the clarity prized by scientific thinking. She manages to celebrate the scientific method, admiring it for its pursuit of truth and knowledge, while allowing knowledge to be undefinable, intangible, and intuitive. This juxtaposition suggests there does not need to be such a divide between the scientific (physical or rational) and the spiritual (immaterial or emotional). In the post-Enlightenment era, continuing on to this very day, there persists a mindset that science and rationality must always be at odds with spirituality and emotions. Af Klint proposes a holistic coalescence of both methods of knowing, a knowledge system that does not dismiss the emotional, intuitive, and spiritual, while still understanding the value of logical assessments and experimentation toward further understanding.

All of the binaries challenged by af Klint in this series of paintings are closely related and tied to a Western colonial, patriarchal perspective which constructed these binaries as methods of control. Her refusal to bend to binaries of gender or knowledge are inextricably linked, as the rational and scientific are often associated with masculinity and the emotional and intuitive with femininity. The latter continue to be devalued in a vicious loop perpetuated by the patriarchy: at times, intuition and emotion are devalued because they’re feminine; other times, women and femininity are devalued because they are too emotional and not rational enough. Af Klint herself was not taken seriously while she was alive because of the deeply spiritual and intuitive nature of her work, which many speculate is partly why she requested her art not be shown until two decades after her death. Af Klint did not just reject binaries, she rejected the entire knowledge system that formed them. This reveals a tension between her, her art, and the society she lived in, and also causes her work to be radical even today. While contemporary Western society has made great strides in understanding of gender, art, and spirituality, it still has yet to shed the constricting knowledge systems that lie at its foundation.

In her Tree of Knowledge series, Hilma af Klint proposes an alternative mode of knowing, a nonbinary knowledge system which sees everything as part of an interconnected whole. This system, as represented by the paintings in the series, rejects notions of inherent difference or separation between things and energies. She saw the world around her as consisting of endless transitions and transformations, a constant give and take between various energies which resulted in existence as seen in everyday life. While Western society has been constructed seemingly out of a fear of multiplicity and fluidity, af Klint embraced those concepts as the essential laws of the universe. Af Klint’s knowledge system is not unfamiliar to many traditions and religions around the world, but to the generally monotheistic, rigid Western culture that she lived in, such a view was at best wacky and eccentric; at worst, an unacceptable rebellion against the status quo. Interpreting her work as such places af Klint’s frequent bouts of isolation into a new perspective and contributes an urgency and relevancy to her artwork in an era of decolonization efforts in the West. Hilma af Klint, through the Tree of Knowledge series, embarked on the experiment of imagining new possibilities and systems, an essential task for all who see the current system as untenable and unsustainable. Destruction of the status quo is not enough: af Klint shows us that creation, imagination, and openness to possibilities beyond our preconceived beliefs are necessary to forge desirable paths into the future.

1. Theosophy is difficult to define, but generally involves the belief that all traditions contain parts of a singular, absolute Truth which can be striven toward through the comparative study of religions, philosophies, and sciences. It was established by Helena Blavatsky in 1875, roughly five years before af Klint would begin her own spiritual journey. The Theosophical Society in America, "Theosophy" (The Theosophical Society in America, 2023)

2. Schwartz, Sanford. "Hilma Af Klint at the Guggenheim." Raritan, 38, no. 4 (2019): 79-92.

3. Carter, Marybeth. "Crystalizing the Universe in Geometrical Figures: Diagrammatic Abstraction in the Creative Works of Hilma Af Klint and C.G. Jung." Jung Journal 14, no. 3 (2020): 147-67.

4. The Greek Myth of the Androgyne, as seen in Plato's Symposium, states that "the natural state of man was not what it is now, but quite different. For at first there were three sexes, not two as at present, male and female, but also a third having both together." Plato. Great Dialogues of Plato. Translated by W.H.D. Rouse. The Penguin Group, 2015.

5. Ryle, Jadranka. "Feminine Androgyny and Diagrammatic Abstraction: Science, Myth and Gender in Hilma af Klint's Paintings." The Idea of North: Myth-Making and Identities 2 (2019): 70-87

6. Af Klint's familiarity with Chinese philosophy could mean this is also a reference to Yin, Yang, and Tao, where "Tao is the One out of which Yin and Yang emerge." Thus, the dual energies of feminine and masculine both emerge from a whole/One and return to it. Low, Albert. The Butterfly's Dream: In Search of the Roots of Zen. Print. Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1993.

7. Schwartz, "Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim."

8. The Scopes trial of 1925, in which a Tennessee teacher was found guilty of violating the law for teaching evolution, underscores the contention around Darwin’s theory of evolution in the early 20th century. Foster, James C. "Scopes Monkey Trial." The First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009. Accessed March 24, 2023.

9. “As the star, glimmering at an immeasurable distance above our heads, in the boundless immensity of the sky, reflects itself in the smooth waters of a lake, so does the imagery of men of the antediluvian ages reflect itself in the periods we can embrace in an historical retrospect. ‘As above, so it is below. That which has been, will return again. As in heaven, so on earth.’”. Blavatsky, Helena P. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology. Print. Vol. 1. J. W. Bouton, 1877.

10. Ryle, Jadaranka. “Reinventing the Yggdrasil: Hilma Af Klint and Political Aesthetics.” Nordic Journal of Art & Research 7, no. 1 (2018).

Bibliography

- Blavatsky, Helena P. Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology. Print. Vol. 1. J. W. Bouton, 1877.

- Carter, Marybeth. “Crystalizing the Universe in Geometrical Figures: Diagrammatic Abstraction in the Creative Works of Hilma Af Klint and C.G. Jung.” Jung Journal 14, no. 3 (2020): 147–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/19342039.2020.1781530.

- Foster, James C. “Scopes Monkey Trial.” The First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009. Accessed March 24, 2023. https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1100/scopes-monkey-trial.

- Low, Albert. The Butterfly’s Dream: In Search of the Roots of Zen. Print. Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1993.

- Plato. Great Dialogues of Plato. Translated by W. H. D. Rouse. The Penguin Group, 2015.

- Ryle, Jadranka. "Feminine Androgyny and Diagrammatic Abstraction: Science, Myth and Gender in Hilma af Klint’s Paintings." The Idea of North: Myth-Making and Identities 2 (2019): 70-87.

- Ryle, Jadaranka. “Reinventing the Yggdrasil: Hilma Af Klint and Political Aesthetics.” Nordic Journal of Art & Research 7, no. 1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.7577/information.v7i1.2629.

- Schwartz, Sanford. “Hilma Af Klint at the Guggenheim.” Raritan 38, no. 4 (2019): 79–92. https://stats.lib.pdx.edu/proxy.php?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/hilm a-af-klint-at-guggenheim/docview/2231401409/se-2.

- The Theosophical Society in America, “Theosophy” (The Theosophical Society in America, 2023), https://www.theosophical.org/about/theosophy.