Conventional wisdom takes it for granted that the more commonplace and everyday something (such as a new technology or concept) becomes, the less capacity it has to enchant. For those living in industrialized nations in the 2020s, computers and networking should be no more mystifying than a newspaper or bicycle. Yet various digital subcultures have sprouted which dedicate themselves to the proliferation of memes which convey something very different: an Internet that is mysterious, unfathomable, and loaded with spiritual meaning. One such memetic subgenre lives under the "divine machinery" tag on tumblr.com. Encapsulating both a visual aesthetic and a diffuse philosophy, divine machinery, even in its specificity and obscurity, is a noteworthy point of analysis in observing how humans are responding to the digital age. The ethereal qualities attributed to the Internet by divine machinery proponents both enfold and respond to the various anxieties provoked by digitalization. Their sentiments point not to a bestowal of occult significance onto the Internet, but a recognition of the Web's pre-existing functions - and potentialities - as an altered state, a form of transcendence, and an alternate dimension that intersects with our own.

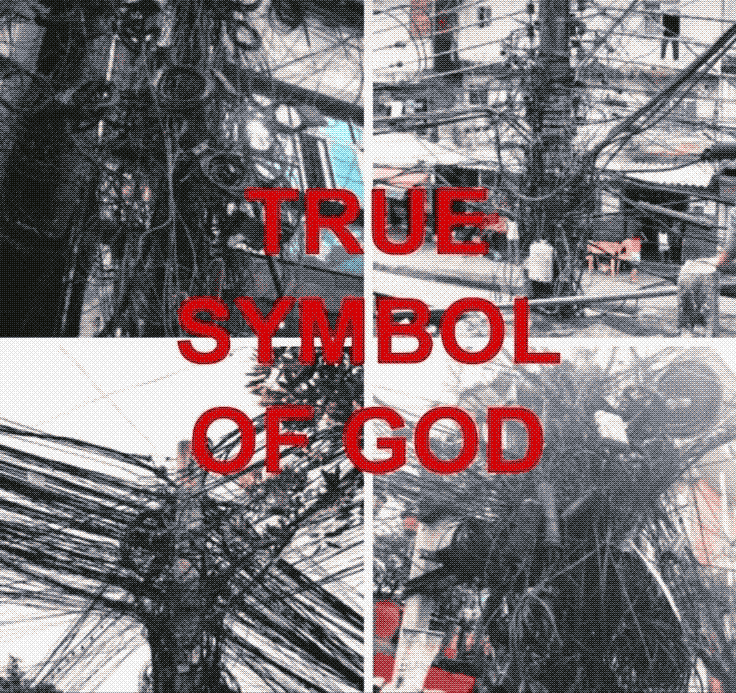

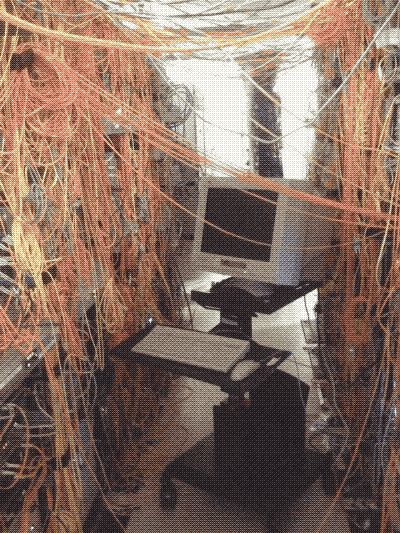

Given its obscurity, divine machinery requires further elaboration prior to analysis. The subculture primarily exists on Tumblr, but can also occasionally be found on Tiktok, X, Reddit, and Pinterest. Little has been written on it from an outside perspective, so the best definition comes from an unvalidated and anonymous entry on Aesthetics Wiki, which describes divine machinery as “compar[ing] technological creation to divine creation, conceptually identifying humanity with god(s) and machinery with angels.” Divine machinery content utilizes a specific set of visuals, with common motifs being tangles of wires and cables, desktop computers, telephone poles, transmission towers, motherboards, and static/glitches in combination with Christian imagery, especially angels and crosses. Divine machinery textposts are typically unpolished but passionate ramblings that “draw connections between biological forms, religious motifs and mechanical structures” (“Divine Machinery”). Though it’s an intense corner of the Internet, there is little evidence in divine machinery content to suggest that participants legitimately “worship” machinery, and it’s unclear how seriously anybody takes the idea. Like the rest of Web 2.0, as described by Damon Young, divine machinery exists in a “contemporary digital culture of an irony of infinite reversibility, of texts that offer no critical vantage point for determining to what extent they mean what they say.” As such, despite its religious motifs and concerns, divine machinery as a whole cannot be approached as a religious belief or practice, but rather is a more concentrated outpouring of emotions that find shape in the meta-exploration of the intersections of theology and technology.

Divine machinery arises at a time in which traditional religions – their promises, rituals, and iconographies – are growing obsolete. In the absence of the stability and assurance once provided by these institutions, the medium of the Internet becomes a governing myth in and of itself. Tumblr user 2-gay-2-furious asks the question: “why should we be interested in angels nowadays?” His answer is “because our universe is organized around message-bearing systems, and because, as message bearing systems, they are more numerous, complex, and sophisticated than Hermes, who was only one person.” This user performs two actions with this post which situate divine machinery in a wider context. First, by questioning why one should be interested in angels – implying there is something outmoded about the concept – and later discounting Hermes as less sophisticated and “only one person,” 2-gay-2-furious responds to and embodies a culture in which traditional myths have lost their relevance and power. Then, his second move is to position communication technology as the figure that fills that void, not only stepping in to fulfill an emptied out space, but in some ways cannibalizing the “old” religions, overtaking them with its sheer omniscience and immediacy, and absorbing their symbology into itself. Because 2-gay-2-furious, as an anonymous individual under a clearly comedic username, makes it impossible for readers to ascertain “speaker meaning,” they cannot assume that his post is sincere – the user himself likely could not determine his own sincerity, either (Young). In many ways, this very “technological reproduction of indeterminacy” is actually key to divine machinery (ibid). Posters in the subculture appear to display a keen awareness of the power they have to create and re-create themselves on the Internet, an act of generative power that would have been unfathomable to pre-digital generations; users become ethereal in their inability to be perceived as earnest or ironic, living in the watery space in between. Under such conditions, religious dogma seems absurd and unfit to capture human experience; and the Internet itself appears to hold a power actually worth considering.

Divine machinery conceptualizes the Internet’s powers in a complicated, multi-faceted manner: the subculture often bestows consciousness and emotion – such as loneliness or sadness – onto individual computers, but also views the realm of the Internet as its own form of expanded and advanced consciousness which materializes as a place, ie. “cyberspace.” Tumblr user newsatnine summarizes this complexity in saying “we created machines in our image, and they transcend us. So much more than us, learning and taking and giving. Kind things, living things. But sometimes, I wonder if static is their way of crying.” In this way, a comparison to Hades may be just as apt as one to Hermes. The Internet is both personified as an angel or a copy of ourselves – as is Hades the god – but is also a transcendent and expansive place – as is Hades the underworld. Divine machinery continues a tradition spawned with the advent of radio communication; wireless “as a popular fantasy of disembodiment [which] suggested that one’s consciousness might someday be free to encircle the earth in a form of electronic omniscience” (Sconce 63). Such fantasies proliferate because the mechanisms of radio and Internet are invisible and difficult to grasp. If they exist in unseeable waves and frequencies which float amongst us at all times – the “etheric ocean” – then it follows that we always share our real-world presence with whatever information is being exchanged over these frequencies (ibid). Such realities are difficult, if not impossible, to truly fathom. So, as with the unfathomability of death, it becomes essential to structure the infinite with readily understandable symbols and metaphors.

The desire for tangible representations of the intangible finds further expression in the iconography of divine machinery. Tumblr user technological-existentialism proclaims transmission towers, telephone poles, computers and supercomputers, circuit boards, robots, and synthesizers as “angels.” The most popular images circulated under the divine machinery tag typically include tangles of cables and 90s-2000s era desktop computers (complete with boxy monitors) (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Though increasingly obsolete, the bulky, physical tools of information technology are at the forefront of divine machinery’s symbolic repertoire. This partly emerges from the aforementioned need to stabilize communication technology, to pin down the ethereal frequencies and signals into something recognizable, understandable, and spatially and materially situated. But there also appears an urge to situate one another, the people interacting over wireless technology, in physical space as well, to reiterate one’s own existence in a wider context of many other existences. From radio’s first days, “the electromagnetic signal stood as a precarious conduit of consciousness and an indexical mark of existence,” conveying transmissions amongst people yet denying the certainty and assurance provided by the physical presence of another (Sconce 67). This feeling has only grown in the Internet age, where people interact with one another with immediacy but often without even hearing one another’s voices or knowing their appearance or their real name. Thus, when images like Fig. 2 are posted with captions and comments such as “you can find me here… if you want…” or “where I post from,” divine machinery exerts two stabilizing forces (angelicmech, fishchips69). It stabilizes the Internet/communication technology into a physical form, and it stabilizes the poster and viewers as corporeal entities, located somewhere in space, recording and typing and very much real.

The language of divine machinery also promises purity, permanence, and transcendence to the user. While a supernatural afterlife appears far-fetched in today’s hi-tech world, a digital or “scientific” one does not. Invisible realities have not only been proven, but are in use by everyday people for purposes as mundane as sharing funny dog videos. Tumblr user gladosluver claims that “if the machine says it’ll love you forever, believe it!! To them, you’ll never die, you’ll live on forever as archived jpegs, chat logs, and command inputs [...] even in death the machine will never forget you...” In tagging this post with #wordsofwisdumb, gladosluver calls their own sincerity into question and enacts a “double negation [that] coincides with telling the truth, a truth that is, however, noncoincident with itself, because it has been unmade and remade through the operations of desire” (Young). Do they believe they’ve approached a core truth in this post or was it simply a cheeky concept they came up with? There could be, and likely are, elements of both to this user’s words, and many others within the divine machinery subculture share this post-ironic approach to transhumanism, once a utopian premise excitedly espoused by techno-philosophers. This ambivalence toward technology’s ability to perfect the human emerges in the juxtaposition of transhumanist language with the biblical (even Catholic) language of humanity’s sinful and uncleanly nature – “[the machines] are cold with wires for intestines and motherboards for brains but they are closer to god than we ever will be and are all that is holy and pure because they are programmed that way” (etceteraetceteraand). Tumblr user labyrinth-walls-tiny-worm contrasts the human body with machines by pointing out the “incorruptibility of inorganic matter” and the “vulnerability of flesh.” Divine machinery appeals to Christianity-derived ideals of perfection, symmetry, and cleanliness, and offers these traits either through the merging of human and machine or by implying that humanity’s ability to create the machine is a form of salvation in itself.

Divine machinery is a relatively hidden niche on the Internet, which most users are probably not familiar with. It is not a mainstream cultural phenomenon, yet it still has much to suggest about culture. Such a niche could not emerge and intrigue if it weren’t for the fact that the Internet imbues the world with a pervasive sense of strangeness, a strangeness first identified in the wireless radio era and exacerbated from that point on. Divine machinery should not be mistaken for a neo-religion emerging from the intersection of technology and spirituality; instead, it is one of many expressions of the destabilizing effect the Internet has had on those cultures which have widely adopted it. The Internet introduces a diffusion and warping of identity, time, space, and reality into the lives of adoptees; as psychologists struggle to understand the possible impacts on the human mind, memetic movements such as divine machinery offer salient insights into the deep philosophical and existential questions posed by the very existence of wireless technology and the ways in which everyday people struggle with them.

Works Cited

- 2-gay-2-furious. "Why should we be interested in angels nowadays?" all about a man, 4 Aug 2024, 10:10 AM.

- angelicmech. "You can find me here..." gabi, 30 Jun. 2024, 10:58 PM.

- "Divine Machinery." Aesthetics Wiki, Fandom, 17. Sept. 2024. Accessed 20 Sept. 2024.

- etceteraetceteraand. "I love divine machinery..." Etc, 10 Jun. 2024, 1:58 PM.

- fishchips69. Comment on "A path cable is loose somewhere." Pinterest, 27 Aug. 2024. Accessed 22 Sept. 2024.

- gladosluver. "If the machine says it'll love you forever..." ryoku, 7 Aug. 2024, 11:57 AM.

- labyrinth-walls-tiny-worm. "Is there really any difference..." labyrinthwalls'tinyworm, 7 Jun. 2024

- newsatnine. "we created machines in our image..." my internet collection box, 27 Jun. 2024, 4:23 PM.

- obeybbpoison. "True symbol of god." swirl, 18 Jul. 2024, 7:25 PM.

- Sconce, Jeffrey. Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television. Duke University Press, 2000.

- technological-existentialism. "Angels are everywhere..." divine machinery, 10 Jan. 2024, 11:38 AM.

- Young, Damon R. "Ironies of Web 2.0." Post45, vol. 2, May 2019. Accessed 20 Sept. 2024.